|

The Celluloid Closet

review by Carrie

Gorringe

The screen version of Vito

Russo's book on the history of the depiction of gays and lesbians in American cinema, The

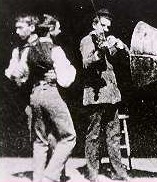

Celluloid Closet, opens on a grainy image. The image is one from American cinema's

proto-cinematic past. Lasting no more than twenty seconds or so on screen, this film

captures in one static shot the spectacle of two men dancing together while a third plays

a fiddle near the base of a large megaphone. Shot in April 1895 and generally known to

film historians by the rather mundane title of Dickson Experimental Sound Film,

this film, (or filmic fragment, depending on your point of view) belongs contextually to

an era of several known levels of potentiality: it represents not only the accomplishment

of being able to present an image and a narrative, however crudely, to a mass audience but

also the attempt to simultaneously provide the final element in a complete movie-going

experience: synchronous sound accompaniment (it was over thirty years in the future). For

Russo, there was yet another potentiality contained therein: the first cinematic depiction

of homosexual activity, and with it, the tacit acknowledgment that gays and lesbians, as

the film's narration tells us, "have always been there." The screen version of Vito

Russo's book on the history of the depiction of gays and lesbians in American cinema, The

Celluloid Closet, opens on a grainy image. The image is one from American cinema's

proto-cinematic past. Lasting no more than twenty seconds or so on screen, this film

captures in one static shot the spectacle of two men dancing together while a third plays

a fiddle near the base of a large megaphone. Shot in April 1895 and generally known to

film historians by the rather mundane title of Dickson Experimental Sound Film,

this film, (or filmic fragment, depending on your point of view) belongs contextually to

an era of several known levels of potentiality: it represents not only the accomplishment

of being able to present an image and a narrative, however crudely, to a mass audience but

also the attempt to simultaneously provide the final element in a complete movie-going

experience: synchronous sound accompaniment (it was over thirty years in the future). For

Russo, there was yet another potentiality contained therein: the first cinematic depiction

of homosexual activity, and with it, the tacit acknowledgment that gays and lesbians, as

the film's narration tells us, "have always been there."

A former archivist at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Vito Russo

began collecting information during the 1970s (some might call it evidence) which

addressed the issue of how gays throughout cinematic history, even during the so-called

"repressive" period of the Production Code (1934 to 1961). His research often

provided inadvertent insights into attitudes toward homosexuality at all levels, some of

which, his writing intimated, he would have been better off for not having. In the

introduction to his book, Russo explains how, during dinner-party discussions of his work,

which he always described as "an exploration of gay characters in American

film", the response he would receive never contained any significant variation in

theme. "Oh, really," his tableside companion would respond, with the

also-invariable leer, "Are you using real people's names?" Whether the setting

was Manhattan or Fire Island, Russo discovered that everyone else was apparently more

preoccupied with a much different form of "telling."

But Russo's intent was never to "out" anyone against his/her

will. Rather, he was trying to amass and organize a substantial amount of evidence which

would testify to the historical existence of gay people; they were not, as certain

conservatives preferred to believe, the product of some form of spontaneous,

post-Stonewall historical generation. By extension, he was arguing for what, for want of a

better term, might be described as the "normalization" of gay life within modern

society. The approach that Russo used was never one of discrimination in reverse, a

tempting response for those who have suffered gross forms of victimization for intrinsic

and unalterable characteristics. Rather than adopting a universal condemnation of all

forms of heterosexuality, he generally took a higher road and directed his anger toward a

more appropriate target: those heterosexuals who were and are intolerant of basic human

rights for gays and lesbians.

And the history of that intolerance, as manifested in American film and

Russo's initial collation of materials, was substantial in scope. Even within the scope of

that very first film clip from Edison's studio, there was a seed of anti-gay derision: as

I recall, both of the men dancing together were doing so in a very self-conscious manner,

as if aware of how socially "aberrant" their behavior was. And, as the film and

book versions of The Celluloid Closet make painfully apparent, the following

decades demonstrated how this original self-consciousness dropped away, leaving only

derision and/or overt hostility as the guidelines for representing Wilde's "love that

dare not speak its name" (since Russo wrote the first draft of the screenplay for the

film version of his book, the film is, not surprisingly, remarkably loyal to its source,

for better and for worse). Indeed, Russo's guided tour through the representation of gay

and lesbian life on screen seems at times less like a history than a Baedecker of social

freaks as compiled by the most rabid homosexists. From the cross-dressing comedies of the

early teens, to the more overt development of the gay male "sissy" that

characterized much of the 1930s (think of a carpally-challenged nebbish whose interests

revolved solely around theatre, fashion and interior decorating with a heavy dose of

lavender), to pathetic creatures ashamed of their gayness who were ready to off themselves

at the first opportunity, gays and lesbians had very few representations in which to take

comfort as far as American film was concerned. The imposition of the Production Code in

1934 arrested most of the more obviously nasty stereotypes, but homosexuality, if conveyed

subtly, was still an acceptable undercurrent in the explanation of a character's physical

weakness, his penchant for bitchy gossip, or her "sinister" sexual tendencies

(such as the bloodsucking Gloria Holden in Dracula's Daughter of 1935). This more

"tasteful" approach was obviously not a concession to gay and lesbian

sensibilities, in its demonstration of how different gays and lesbians were from

"normal" society (and, if such people really did exist outside a movie screen,

heterosexuals could rest assured that, armed with a set of codes from Hollywood films,

they could decipher and detect homosexuals before they could do any "harm").

When younger filmmakers working in the mainstream during the 1950s tried

to bring more balance and maturity into attempts to address homosexuality on screen, such

boldness acted as a red flag to the censors, who would then wield their blue pencils with

more vigor. Among the casualties of bowdlerization were important works like the screen

adaptation of Tea and Sympathy (in the play, it was quite obvious that the young

man feared being gay; in the 1956 film, only the most subtle of hints about his

"manhood" were permitted). Even the lifting of the final Production Code

restrictions did not result in realistic representations of homosexuality; in William

Wyler's remake The Children's Hour (1962), based on Lillian Hellman's play of the

same name, poor Shirley MacLaine still must suffer the slings and arrows of

"compensating moral values" and commit suicide as penance for discovering the

lesbian side of her character. When MacLaine talks about the film thirty-four years later,

she makes it clear that there was so little awareness on the set as to what constituted a

lesbian lifestyle that no one even discussed the subject during the shoot. Despite the end

of de jure censorship, the de facto version prevailed, and the countervailing images of

gays and lesbians as either unhappy and suicidal or sexually rapacious continued, for the

good reason that many gays and lesbians in the film industry, as in life, could see no

sense in coming out of the closet only to find themselves in the crosshairs of social

disapproval. Until very recently, with the arrival of openly gay filmmakers like Gus Van

Sant, who were not reluctant to let their sensibilities flow in front of the camera, the

prejudice continued unabated, with very few, if any depiction's acting as a counterweight

to the mountain of negative images, and the clearing isn't really in sight.

Obviously, The Celluloid Closet is an ardent defense of the

right of gays and lesbians to see truthful images of themselves. At times, this ardor is

one of the few quibbles I have with The Celluloid Closet in either form: in their

pursuit of truth, both occasionally attempt to stretch it somewhat beyond reason. The

aforementioned experimental film from 1895 has some greater historical significance than

merely showing two men dancing together. As stated earlier, the film was shot in April

1895 by inventor (and Edison employee) W.K.L. Dickson as part of a vain attempt to save

Edison's dwindling Kinetoscope business (an early film viewer -- essentially nothing more

than a peep-show device, albeit large and cumbersome) by marrying image to sound. The film

may have picked up the title proffered by Russo -- The Gay Brothers -- elsewhere,

or it may have been an unofficial title, but the chief issue for film historians, and for

the film's participants, was one of sound, not sexual orientation (to those who would

seize upon this "omission" as first-hand evidence of homophobia in film studies,

I would respectfully suggest that there are many film scholars currently at work who would

have more than a vested interest in bringing to light any "neglected" truths

about this film, or any film, for that matter). On the most basic level, the two men might

have danced together simply because no woman was available at Edison's studio for the

purpose; there currently exists no evidence to prove otherwise. Whatever the case may be,

the film was probably never seen outside of the studio. Nevertheless, Russo provides no

background information to substantiate his choice of title, and Epstein and Friedman

merely repeat Russo's assumptions about the film verbatim, if for no other reason than it

is (if my memory and the sources I have investigated are correct) probably the only piece

of pre-1900 footage that displays two men in very close contact, thereby sustaining

Russo's thesis. Ironically enough, had Russo, Epstein and Freedman actually made only the

slightest of additional efforts to investigate other films made by the Edison company at

the same time, they would have found films that fit the hypothesis just as neatly and with

less historical uncertainty. Foremost among them were the frequent studies of the

then-renowned strongman Sandow, who always posed and performed in medium-close-up, bulging

muscles and bared midriff at the ready. Moreover, no less an authority on pre-1900 cinema

than Charles Musser has concluded that the earliest films were made "by men and for

men", thereby providing a strong case for Russo's assertion that gays were probably

present at the cinematic creation. But while this experimental film may or may not have a

gay subtext, it certainly does neither version of The Celluloid Closet any credit

to make claims that may not have any basis in fact.

Unfortunately, as Russo, Friedman and Epstein have quite ably

demonstrated, there is more than enough evidence of a homophobic mentality operating

throughout Hollywood's history to make up for any overeager leaps of logic. And some of

the worst stereotypes, ironically enough, occurred in the 1960's and especially in the

1970s, a period long outside the domain of the Production Code, but well within the

boundaries of the first flowering of Gay Liberation. Screenwriter Ron Nyswaner recalls the

words hurled at him as he was escaping from a gay-bashing, an episode that occurred just

after William Friedkin's controversial movie, Cruising (1980) was released. One

of Nyswaner's attackers, who worked in a movie theatre, yelled after him, "If you saw

the movie Cruising, you'd know what you deserve" -- perhaps to be

dismembered and floating in the Hudson River, a la the film's opening scene.

The recounting by Nyswaner of his harrowing brush with sociopathic

hate-mongers is illustrative of perhaps the most problematic issue for The Celluloid

Closet, one that also speaks directly to the most recent series of demands for

censorship of U.S. television and the Internet. Both of them revolve around the concept of

how images -- and the inclusion of only the visual in this case is deliberate -- influence

behavior. Underlying this concept is the assumption that the interpretation of images is

always universal and unequivocal, or, to put the matter more simply, everyone sees

everything in the same way, an assumption that has been challenged by students of

propaganda such as Ellul, et al, who have adduced beyond all reasonable doubt that

propagandistic techniques must effectively address the expectations and prejudices of

their intended audiences (it goes without saying that propagandists can persuade others to

accept other messages, but the process is slower, with more risk, and the new messages

still cannot stray too far from their audience's sensibilities). In other words, (pace

Althusser) propaganda is not a one-way form of communication shoved down the throats of

the "mindless" masses; the same "mindless" masses must participate in

their own "persuasion", as it were, by bringing something to the table, in each

case something that is affected by any number of non-media-based influences. Images alone

cannot be presumed to be the sole source of influence upon humanity in general, but the

acceptance of and/or lack of overt resistance to certain cultural underpinnings,

individually and en masse, is a key factor. Many of the commentators in The Celluloid

Closet correctly (and sometimes inadvertently) note the diverse ways in which images

were interpreted by audience members like themselves; screenwriter Arthur Laurents and

actor/screenwriter Harvey Fierstein have an on-screen dispute (courtesy of contrapuntal

editing) over the stereotype of the sissy which is quite illuminating in this regard

(Laurents loathes the sissy, while Fierstein takes a somewhat perverse pride in it).

But neither version of The Celluloid Closet is inclined to

accept this insight, because, in doing so, they would undercut their own message: the

belief, as spoken by Tomlin, that "Hollywood, that great maker of myths, taught

straight people what to think about gay people...and gay people what to think about

themselves." So, in following this argument to its logical conclusion, if negative

images provoke negative behavior, then centuries of hatred can be undone with the advent

of purely positive images. From this unspoken assumption, the film ends up presenting an

antipodal "chicken-and-egg" argument as it tries to prove simultaneously that

the images cause hatred and the hatred causes the images. What the film ends up doing on

occasion is chasing its own tail. In actual fact, the homophobia of Cruising and

other anti-gay films is nothing more than a reflection of beliefs already in play among

certain members of their audiences; using them as a cover for sanctioning discrimination

or violence against gays and lesbians is no less loathsome than the initial impulse to

cause harm. Therefore, the fear that the cinematic version of The Celluloid Closet,

or any film with a pro-gay message, will end up speaking only to the converted becomes, in

this case, the fear that dare not speak its name. But one can't whitewash a questionable,

if good-intentioned, ideology with a patina of excessive optimism. Despite the moral

rectitude of Russo's position on tolerance for gays and lesbians, Epstein and Friedman

must come to realize that this film is only one step in a very long journey, and not the

"ne plus ultra" in terms of persuasiveness.

Nevertheless, The Celluloid Closet is an entertaining and

invaluable document, and, despite its various missteps, no less of an indictment of

homophobic tendencies in the larger society. Particularly interesting are the excerpts

from the pre-Code films, items which are rarely seen and rather shocking in their sexual

candor, even to contemporary audiences. Some of the interviewees listed above provide, in

the course of their candid discussions, valuable insights into how the Production Code

affected their professional and personal lives. In particular, Gore Vidal is a most

compelling raconteur; his explanation of how the first chief of Hollywood's self-imposed

censorship body was chosen in 1922 ("at that time there were a number of unindicted

members of [Harding's] cabinet...") hilariously eviscerates any pretense surrounding

the impulse to censor. Moreover, Vidal's explanation of how he was able to implant a

subtle homosexual subtext in the relationship between Stephen Boyd and Charleton Heston in

Ben-Hur (1959) is worth the price of admission by itself, likewise Maupin's

commentary on Rock Hudson's on-screen persona. Over the film's credits, K.D. Lang sings a

reprise of the song Secret Love, associated with Doris Day and the 1953 film, Calamity

Jane, itself associated with a not-so-covert set of lesbian underpinnings in certain

scenes. And if, in the forty-three-year span of time between Day and Lang, the

"secret love" of gays and lesbians has become more of a secret opened than an

open secret, it still has a long way to go before it is "no secret anymore." In

this regard, The Celluloid Closet can take no little credit for detailing the

progress that has been made, as well as enumerating what needs to be done.

|

|

Directed

by:

Rob Epstein

Jeffrey Friedman

Narrated

by:

Lily Tomlin

Commentary

by:

Shirley MacLaine

Armistead Maupin

Harvey Fierstein

Gore Vidal

Richard Dyer

Tom Hanks

Arthur Laurents

Tony Curtis

Jan Oxenberg

Matt Crowley

Whoopi Goldberg

John Schlesinger

Susan Sarandon

Ron Nyswaner

Jay Presson Allen

Paul Rudnick

Susie Bright

Written

by:

Rob Epstein

Jeffrey Friedman

Sharon Wood

Vito Russo

FULL CREDITS

BUY

VIDEO

RENT

DVD

BUY

MOVIE POSTER |

|