|

| |

L.A. Confidential

Review by Carrie

Gorringe

Posted 19 September 1997

|

|

Directed by Curtis Hanson Starring Kevin Spacey, Russell Crowe,

Guy Pearce, James Cromwell, David Strathairn,

Kim Basinger, and Danny DeVito

Screenplay by Curtis Hanson and Brian

Helgeland,

based on the novel by James Ellroy |

"It’s paradise on

earth…that’s what they tell you, anyway." So begins the narrative of Guy

Hudgeons (DeVito), as grainy color pictures of the glittering utopia known as Los Angeles

in the 1950s flash past the audience’s eyes. Swimming pools, no snow and all the

oranges you can eat – a post-war fantasy when the price of admission was accessible

to many. Listen and look a little closer, however, and the rot within begins to bubble up

like a sudden shift in the San Andreas Fault. It’s not the only fault in L.A., and

Hudgeons knows that very well. As the publisher of a tell-all tabloid, Hudgeons

doesn’t simply dish dirt about the underside of Hollywood glitter, he shovels it by

the truckload. He gets his info. from the inside; Sargent Jack Vincennes (Spacey) of the

LAPD, a gentleman who serves both the Hollywood community (as a technical adviser to a TV

crime drama) and serves the law, in a more nominal sense, also decides to serve himself.

When indiscretions occur, Vincennes is quick to contact his old friend Hudgeons, who is

conveniently on the spot when the arrests for narcotics possession or prostitution take

place. It’s a nice little deal for everyone concerned, except for the victims.

But Vincennes has

run up against two other members of LA’s finest, who don’t like either him or

his methods. Ed Exley (Pearce), the son of one of the force’s most-revered

detectives, hates Vincennes’ ambiguous approach to duty. Bud White (Crowe), a

hard-drinking and harder-brawling version of Exley, probably resents Vincennes’ fame

as much as he despises Vincennes’ snidely urbane demeanor. The paths of all three men

cross one night at the Nite Owl Café, where a massacre takes place, and a racist cop is

killed. An investigation leads the detectives into the world of high-class prostitution,

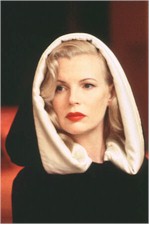

in the guise of the alluring Lynn Bracken (Basinger), her pimp, Pierce Patchett

(Strathairn), and into corruption at the highest government levels. Whether or not either

touches their chief, Dudley Smith (Cromwell), is a question they may not be able to

answer. But Vincennes has

run up against two other members of LA’s finest, who don’t like either him or

his methods. Ed Exley (Pearce), the son of one of the force’s most-revered

detectives, hates Vincennes’ ambiguous approach to duty. Bud White (Crowe), a

hard-drinking and harder-brawling version of Exley, probably resents Vincennes’ fame

as much as he despises Vincennes’ snidely urbane demeanor. The paths of all three men

cross one night at the Nite Owl Café, where a massacre takes place, and a racist cop is

killed. An investigation leads the detectives into the world of high-class prostitution,

in the guise of the alluring Lynn Bracken (Basinger), her pimp, Pierce Patchett

(Strathairn), and into corruption at the highest government levels. Whether or not either

touches their chief, Dudley Smith (Cromwell), is a question they may not be able to

answer.

L.A. Confidential is the latest entry in the post-Chinatown series of

films. Last year saw Mulholland Falls and Devil in a Blue Dress meet fiscal fates as tragic as those

of their characters. To answer the question of why they failed will answer the question of

why L.A. Confidential will succeed. The first answer lies in the prototype for all

of these films: Polanski’s 1974 film noir classic, in a nutshell, was not only

a standout in terms of its retrospective subject matter (Chinatown was released in

an era of films that were more concerned with temporary corruption, or 1950s nostalgia, so

it presented a distinct alternative to what was available), but also in its attitude

toward the nature of systemic corruption.  Both Chinatown and L.A. Confidential have as their basis an

understanding that corruption is not extraordinary in its evil, but rather comes about as

a series of initial compromises that snowball into greater compromises; the effect upon

its victims may be sudden and merciless, but the process by which it attains its strength

certainly isn’t. By contrast, Mulholland Falls wanted us to focus on the

national scope of evil (atomic secrets) and Devil in a Blue Dress emphasized the

quotidian nature of racism. Devil came closest to succeeding simply because racism

works as insidiously as corruption upon the minds of those infected by it. But Mulholland,

like Devil, tried to deliberately underscore the national scope of the evil. Film noir

works best when the evil is revealed in all of its facets, but only on the most localized

of bases. Only after a screening should the audience begin to piece together the awful

implications of several facets of localized evil operating simultaneously. The genre

thrives on inductive, not deductive methods. Go to the general picture too quickly, and

the audience loses sight of the process, because it loses sight of identification with the

main characters and their situations. Both Chinatown and L.A. Confidential have as their basis an

understanding that corruption is not extraordinary in its evil, but rather comes about as

a series of initial compromises that snowball into greater compromises; the effect upon

its victims may be sudden and merciless, but the process by which it attains its strength

certainly isn’t. By contrast, Mulholland Falls wanted us to focus on the

national scope of evil (atomic secrets) and Devil in a Blue Dress emphasized the

quotidian nature of racism. Devil came closest to succeeding simply because racism

works as insidiously as corruption upon the minds of those infected by it. But Mulholland,

like Devil, tried to deliberately underscore the national scope of the evil. Film noir

works best when the evil is revealed in all of its facets, but only on the most localized

of bases. Only after a screening should the audience begin to piece together the awful

implications of several facets of localized evil operating simultaneously. The genre

thrives on inductive, not deductive methods. Go to the general picture too quickly, and

the audience loses sight of the process, because it loses sight of identification with the

main characters and their situations.

Moreover, L.A.

Confidential and Chinatown share a more intimate understanding of how personal

the effects of evil really are. Polanski’s nightmarish personal life (his

mother’s death in Auschwitz, his wife and unborn child’s slaughter at the hands

of the Manson Family) obviously shaped the cynical acceptance of corruption as inevitable

that permeates Chinatown. Ellroy, whose mother was murdered by an unknown assailant

in the late 1950s, also knows the personal cost of evil’s arbitrary nature. Both

films seethe with rage at the sequence of malevolent events that engulf their characters,

but most of the rage is trapped in confusion and pain that renders its characters unable

to act against that which will destroy them. This is the source of moral ambiguity that

makes film noir fascinating to anyone who can stand to watch. Remove this mixture of

elements and you gut the film of its most vital force, rendering it nothing more than a

mere murder mystery. Moreover, L.A.

Confidential and Chinatown share a more intimate understanding of how personal

the effects of evil really are. Polanski’s nightmarish personal life (his

mother’s death in Auschwitz, his wife and unborn child’s slaughter at the hands

of the Manson Family) obviously shaped the cynical acceptance of corruption as inevitable

that permeates Chinatown. Ellroy, whose mother was murdered by an unknown assailant

in the late 1950s, also knows the personal cost of evil’s arbitrary nature. Both

films seethe with rage at the sequence of malevolent events that engulf their characters,

but most of the rage is trapped in confusion and pain that renders its characters unable

to act against that which will destroy them. This is the source of moral ambiguity that

makes film noir fascinating to anyone who can stand to watch. Remove this mixture of

elements and you gut the film of its most vital force, rendering it nothing more than a

mere murder mystery.

Needless to say,

Hanson gets the blend just right in L.A. Confidential. The film is replete with

deceit, but much of it isn’t readily apparent. The film starts out with some

characters clearly aligned between those who walk the line of the law and those who skirt

it, some with less abandon than others, but the straight line soon proves to be nothing

more than a wave on a moral oscilloscope, wildly fluctuating from situation to situation.

The appearance of complexity is simply that, and the simplistic is most likely to become

the most complex. Those who can’t adjust to the constantly changing landscape, like

the intractable White, will find their lives irreparably shaken. To describe the process

in anything but the vaguest terms is to reveal too much, but this is the overall effect

that Hanson and Ellroy provide to the audience – quintessential film noir, and

it’s a masterful work. Needless to say,

Hanson gets the blend just right in L.A. Confidential. The film is replete with

deceit, but much of it isn’t readily apparent. The film starts out with some

characters clearly aligned between those who walk the line of the law and those who skirt

it, some with less abandon than others, but the straight line soon proves to be nothing

more than a wave on a moral oscilloscope, wildly fluctuating from situation to situation.

The appearance of complexity is simply that, and the simplistic is most likely to become

the most complex. Those who can’t adjust to the constantly changing landscape, like

the intractable White, will find their lives irreparably shaken. To describe the process

in anything but the vaguest terms is to reveal too much, but this is the overall effect

that Hanson and Ellroy provide to the audience – quintessential film noir, and

it’s a masterful work.

This film also has

one of the best casts available. It’s really difficult to rate any of the

performances, because all of them are absolutely perfect in their roles. If there is a

standout, however, it really has to be Basinger, who displays more tenderness and steel

than she has in many years. This should put an end to whatever stalls her career may have

suffered. As the constant and ironic refrain that echoes throughout the film (Johnny

Mercer and The Pied Piers accentuating the positive) emphasizes, there are a lot of

positives to be had from accentuating those negatives. At the beginning of L.A.

Confidential, Chief Smith tells the politically ambitious Exley, "You have the

eye for human politics, but not the stomach." This film covers both sides of that

street with ease. This film also has

one of the best casts available. It’s really difficult to rate any of the

performances, because all of them are absolutely perfect in their roles. If there is a

standout, however, it really has to be Basinger, who displays more tenderness and steel

than she has in many years. This should put an end to whatever stalls her career may have

suffered. As the constant and ironic refrain that echoes throughout the film (Johnny

Mercer and The Pied Piers accentuating the positive) emphasizes, there are a lot of

positives to be had from accentuating those negatives. At the beginning of L.A.

Confidential, Chief Smith tells the politically ambitious Exley, "You have the

eye for human politics, but not the stomach." This film covers both sides of that

street with ease.

Contents | Features

| Reviews | News | Archives | Store

Copyright © 1999 by Nitrate Productions, Inc. All Rights

Reserved.

| |

|